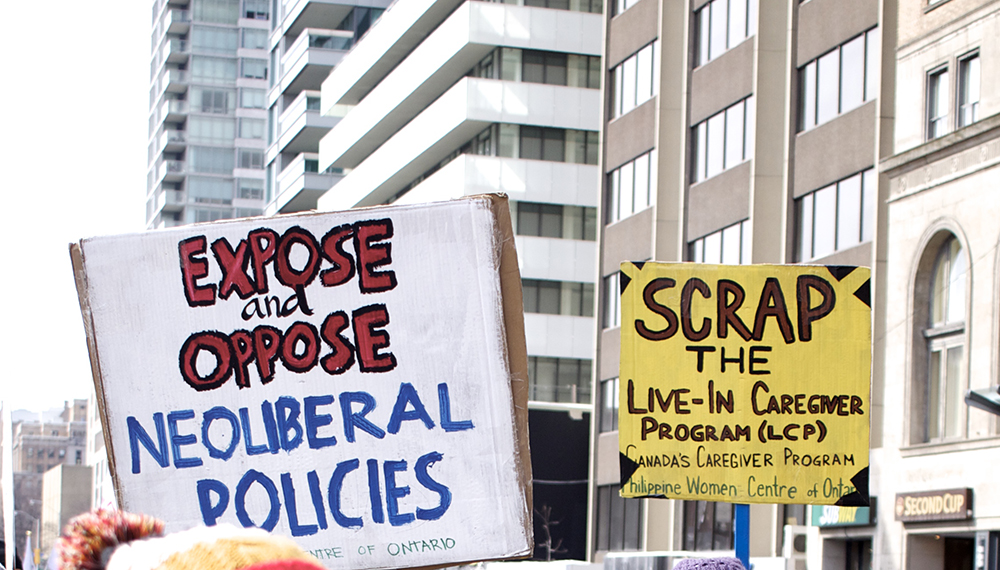

The history of recruiting immigrant workers to fill Canada’s caregiving needs has also coincided with a history of these workers uniting to demand basic rights, and fighting against the exploitative conditions of immigration policies like the Live in Caregiver Program. The focus of these movements have continuously been on caregivers rights to obtain permanent residency. This is seen from the movements in the 1980s that demanded the implementation of policies to guarantee foreign caregivers rights for permanent residency that led to the creation of the Foreign Domestics Movement and subsequently the LCP, to current activism efforts calling for permanent residency upon arrival, and scrapping the LCP altogether.

The call to end the LCP was ultimately acknowledged in 2014 when the federal government closed the program to new applicants. The LCP was replaced with two alternative pathways for foreign caregivers to obtain permanent residency. These included the Caring for Children, and Caring for People with High Medical Needs pathways. This has eliminated certain problematic aspects of the LCP like the live-in requirement. However, this is not enough to protect caregivers as their status in Canada is still dependent upon their employers, something that permanent residency upon arrival would address. In addition, the new structuring of the program places restrictions to caregivers entry into Canada. This includes capping the entry of caregivers in each pathway to much lower numbers than through the LCP. Further, the new pathways also include tougher requirements that presents additional barriers for caregivers.

“The Canadian government wants superwoman to take care of Canadian families but refuses to give them good wages and security of status in return”

Coco Diaz

This has led to the continuation of demonstrations, lobbying, and activism for the rights of these foreign caregivers in Canada, calling for permanent residency upon arrival and the end of neoliberal based policies that foster the unfair treatment of these workers.

As a result of the inadequacy of the 2014 changes the Liberal government has recently introduced two new pilot programs that allow caregivers the ability to obtain permanent residency through either the Home Child Care Provider pilot or the Home Support Worker pilot. These programs claim to give caregivers the freedom to change jobs quickly, provide them the opportunity to bring their families with them to Canada, and access permanent residency after twenty-four months. Although these changes may address some of the previous problems faced with the LCP, it still fails to recognize the systemic issues creating the exploitation of these workers, and the importance of granting them permanent residency upon arrival so they are not vulnerable to certain unfair or abusive work environments.

The fact remains that caregiving within our society has and still is undervalued, underpaid, and feminized. This lack of recognition of caregiving will likely remain invisible as long as women continue filling these roles. Further, the structural relationship of the LCP continues to be present within these new changes, which suggests that the exploitative nature of this work will continue.